Disclaimer: Please be aware that the article contains spoilers.

When signing a lease in 1898, a British diplomat settled for the proposed period of 99 years of tenancy because, in his words, this period “seemed like forever”. However, the British forces did not really know what to do with a rocky region where a small fishing town was located. It was not until the 1950s when, following the principles of free-market capitalism, Hong Kong was set on the path of rampant economic development, ultimately becoming the paragon of laissez-faire policies in action. Nevertheless, the lease period was already well halfway through. In 1984, the British officials met with the Chinese authorities and they negotiated the handover agreement. Hong Kong was to go back to the People’s Republic of China, but its system was to remain unaltered for the next 50 years. On July the 1st, 1997, Hong Kong ceased to be a British colony and became the Special Administrative Region of the PRC.

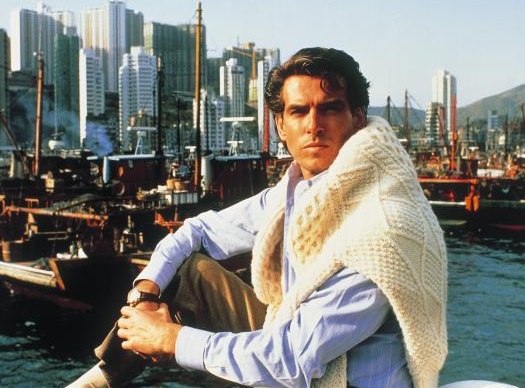

This political change made a great impact on the local movie industry, resulting in many small/medium-sized companies going bankrupt and the big players undergoing restructuring. Interestingly, no motion picture directly focused on the looming handover event before 1997. What can be observed in such films are shy allusions. For instance, Her Fatal Ways (1990-1994) is a series of comedies which explores the strained relationship between mainlanders and Hong Kong citizens, and we can repeatedly see many supporting characters voicing their worries about what will happen after 1997. In addition, Michael Hui’s comedy Front Page (1990), opens with a montage of Hong Kong’s everyday hustle and bustle, which is accompanied by an upbeat song “I don’t care about 1997”. There is also a miniseries based on James Clavell’s novel Noble House which, under its espionage plotline, attempts to underline the fact that Hong Kong is distinctly British, and no outside influence shall ever change it.

|

|

Indeed, Hong Kong used to be the place of British high-rollers, legal horse racing, and Rolls Royces, but the situation has changed after the transfer of power. The British had to leave after 150 years of presence in Hong Kong. In the new reality controlled by the PRC, ordinary citizens, businessmen as well as filmmakers had to find their own way.

Enter the three motion pictures which, in fact, did address the 1997 transfer of power shortly after it took place. That is Fruit Chan’s The 1997 Trilogy, a set of movies made between 1997 and 1999.

The first one, Made in Hong Kong, as the title ironically suggests, is the first independent film released in post-British Hong Kong (made out of leftover film tape). The story of the film focuses on youngsters who are social outcasts. The main protagonist, Autumn Moon (Sam Lee), is a worthless misfit who collects debts for the triads. He frequently protects his friend, Sylvester (Wenders Li), who is mentally-challenged. Together, they meet Ping (Neiky Yim Hui-Chi), a resident of a public rental housing estate. The trio accidentally gets into possession of letters written by a certain Susan (Amy Tam Ka-Chuen), a high school girl who committed suicide. The friends try to deliver the letters to respected addressees.

In Made in Hong Kong, Fruit Chan explores the lives of people at the very moment of great changes. The British are leaving and the Chinese have not arrived yet, the people of Hong Kong are left to themselves and they are actually deprived of identity. Autumn Moon tries to do anything in his life, literally anything, like becoming a killer for the triads, but he is unable to kill anyone. Fruit Chan stated in an interview that Moon desperately wants to live, but he is incapable of living in such a world; Ping also wants to live, but she suffers from cancer; Sylvester is unable to live because of his limitations; whereas Susan kills herself because she can’t think for herself.

In a desperate attempt to avenge the untimely death of Sylvester, Moon confronts the triad leader, and while pointing a gun at him says: “I remember that you said that the world is now ruled by the young. Now, I’ll show you!” and he kills the gangster. Vivienne Chow claims that this one scene is the prophetic foreshadowing of the attitudes represented by the 2019 HK protesters. With Made In Hong Kong, the director successfully provided "a look at youthful alienation in the period" before the transfer of sovereignty over Hong Kong, but he also subconsciously emphasised that Hong Kong is essentially a parentless state. Loss of identity takes place because it is neither British nor Chinese. The only way for Hong Kong to move on is to forget about its roots.

It has to be noted that director Fruit Chan really has an eye for visuals. One could think that there is nothing appealing in small apartments, huge high-rises with courtyards, or cemeteries, yet the dream-like atmosphere of Made in Hong Kong combined with these images is truly captivating.

With regard to performances, Fruit Chan worked on each entry of the 1997 Trilogy with non-professional actors and actresses. Allegedly, it took them months of rigorous rehearsals before the crew could start shooting. Nevertheless, all of the performers involved did a fine job. In fact, the movie marks the debut of Sam Lee who, thanks to his memorable performance as Moon, went on to have a successful career. He also appeared in Fruit Chan’s subsequent movies.

The movie that followed, The Longest Summer, is perhaps the only Hong Kong production which openly addresses the handover of power, even to such an extent that the handover ceremony itself is shown in the film. The story revolves around 5 officers of now disbanded Hong Kong Military Service Corps. Jobless and with no prospects, the retired officers decide to rob a bank, but in such a way that no one will get hurt. Surprisingly, the bank is robbed by another team of bandits just moments before the protagonists are about to enter the building. However, they manage to snatch the stolen cash and hide it. All of that happens during the transfer of power.

The main hero, Ga Yin (Tony Ho), is informed by his triad boss that Hong Kong turned into a baby within the span of just one day. Indeed, this change is observable with the singing of Auld Lang Syne in two languages and with the arrival of the People’s Liberation Army. Because of the stolen money, the officers start to distrust each other and Ga Yin’s brother (Sam Lee) goes missing with the loot (he is presumably killed by mobsters). Devastated Ga Yin goes crazy and attacks a random triad member, trying to teach him a lesson. However, he gets shot in the course of the fight. Ga Yin actually survives, but he loses memories of his lost brother and his service in the British Army. He involuntarily starts afresh as a delivery man in new Hong Kong.

The Longer Summer is, in my opinion, Fruit Chan’s best motion picture. The director managed to craft a dynamic drama in which the main protagonist has to give up his entire identity, his own subconscious, in order to be able to embrace the new state of affairs. As a result, it can be inferred that the colonial legacy of Britain as well as the Chinese advent of communism are nothing more but ideological burdens.

In the final movie, Little Cheung from 1999, Fruit Chan provided an autobiographical look at the life of a typical hardworking family. In the style similar to Edward Yang and Hirozaku Koreeda, the director paints a portrait of children of Hong Kong. They may be poor, they may be working on the streets, but they remain unconcerned about grand historical events happening around them. One of the most interesting subplots of the film is Little Cheung (Yiu Yuet-Ming) and his grandmother’s (Chu Siu-Yau) obsessive fascination with a classic opera singer “Brother Cheung”. The Pilipino maid in the house accurately notices that the family would care more about the death of this singer, rather than the death of Deng Xiaoping himself. In this way, Fruit Chan communicates that being Chinese does not mean being an ideological communist by default. Communists do not understand ordinary life, which is reflected in yet another scene where Cheung together with his friends scream at Hong Kong downtown in the distance: “Hong Kong is ours!”.

Nevertheless, changes do take place in Little Cheung’s life. His grandmother dies, the nanny moves away, and his friend, a girl called Fan (Mak Wai-Fan), is deported because she’s an illegal immigrant. With the approaching handover of power, Little Cheung’s childhood drastically comes to an end. He has to find his own voice in a new world. Ironically, in a twist similar to the conclusions of grand epics by Krzysztof Kieślowski, the protagonists of all three films encounter each other at a zebra crossing in the concluding scene of Little Cheung. After all, the citizens of Hong Kong constitute its future.

All things considered, the people of Hong Kong are indeed torn between two political systems and their emotions are communicated not only on the streets but in culture as well. Over 20 years after their original release, Fruit Chan’s independent movies are especially important in view of the 2014 Umbrella Movement and the 2019 protests. Hong Kong has its own distinct history and identity. It is not a good-for-nothing province: “Tony Blair has just been elected Prime Minister and he and his foreign secretary were totally uninterested. In the pouring rain, they were looking at the military parade from underneath their umbrella, for the transfer at midnight. Their entire attitude signalled something like: 'Can we go now?' That was it for the once great British Empire” (source).

Note: In order to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the film, L’Immagine Ritrovata made a 4K restoration of Made in Hong Kong in 2017. The Longest Summer and Little Cheung are available in Standard Definition.

Sources: An End and a Beginning: Fruit Chan’s Made in Hong Kong * On Made in Hong Kong * The Future of the Past: On Fruit Chan and Made In Hong Kong * Decolonial Moments in Hong Kong Cinema * Bruce Gilley Interview * Fruit Chan Interview